18 Mar Entering Kṛṣṇa-Līlā – Part 2

Courtesy of Śrīla Sanātana Gosvāmī and Śrī Gopīparāṇadhana Prabhu

Let’s give our attention, in the way proposed in part one, to the next verse:

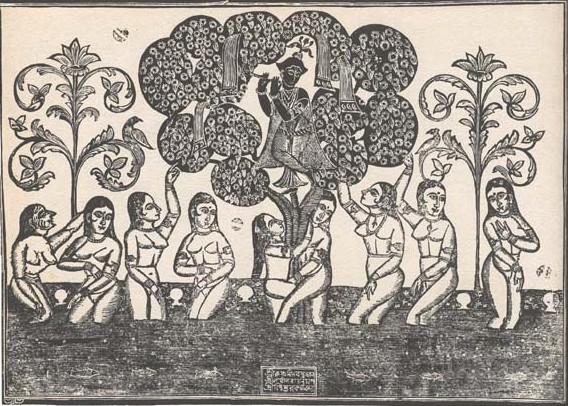

To properly conclude their vrata, the gopīs disrobe on the bank to bathe within the Yamunā’s water. Immersed in the stream, they discover the very person they had all sought as husband reposing at ease on a high branch of a riverside kadamba tree, looking down upon them. All their garments, left behind on the bank, now rest in a heap next to Kṛṣṇa on the tree limb.

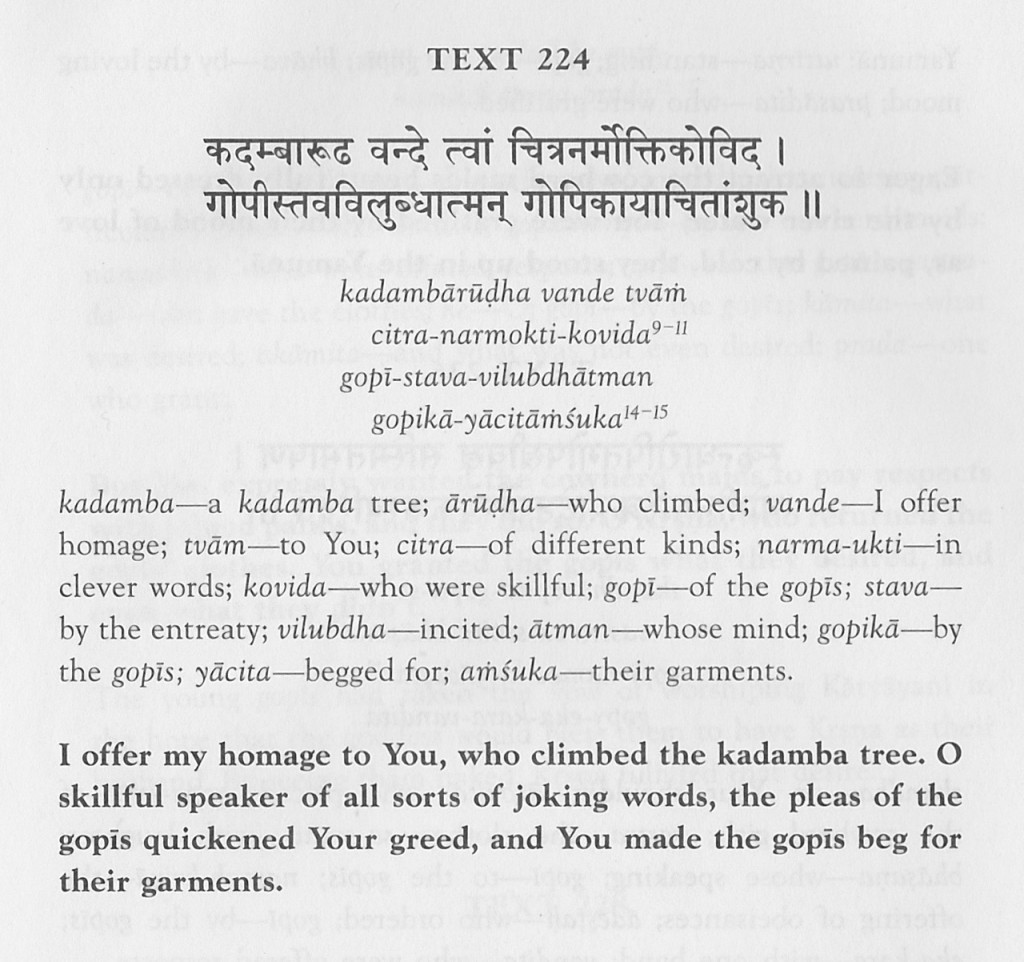

Sanātana Gosvāmī pays homage to Kṛṣṇa (vande tvām) as kadamba–arūḍha, “the climber of the kadamba tree.” Sanātana Gosvāmī’s act of vandanam here heightens our realization that the narration conveys the author’s own remembrance of and meditation on this pastime as he has heard or read it in the Śrīmad Bhāgavatam. Thus his single line expresses a fusion of śravaṇam, kīrtanam, smaranam, and vandanam, four of the nine elements of bhakti.

In the rest of this text, covering Bhāgavatam verses nine through fifteen, Sanātana Gosvāmī refines the narration into three names of Kṛṣṇa, with which he calls out to ḥim:

citra-narmokti-kovida: One skillful (kovida) at talking (ukti) in funny, high-spirited (narma) and wonderfully ingenious (citra) ways.

gopī-stava-vilubdhātman: One whose heart or mind has become greatly aroused or incited (vilubdha) by the pleas (stava) of the gopīs. Notice the use of the word stava to denote the entreaties of the gopīs as recorded in the Bhāgavatam: dehi vāsāṃsi, “Give us our clothes!” Stava (derived from the Sanskrit verbal root √stu, to praise or eulogize) means “hymns of praise,” so it may seem an odd word to use in this case. However, the gopīs at heart are rejoicing, and stava reveals their mentality. The word also alludes to the transcendent nature of what may seem a naughty prank by a village boy. And it also points to the connection between the ecstatic feelings of the gopa–kanyās and of the author himself—between the gopī’s stava and the author’s own Śrī Kṛṣṇa Līlā Stava.

gopikā-yācitāṁśuka: You who are entreated or beseeched (yācita) for the return of their clothing (āṁśuka) by the gopīs. Gopīparāṇadhana dāsa: “You made the gopīs beg for their garments.” The “made” is implicit in the original: someone is beseeched only when something wanted is withheld.

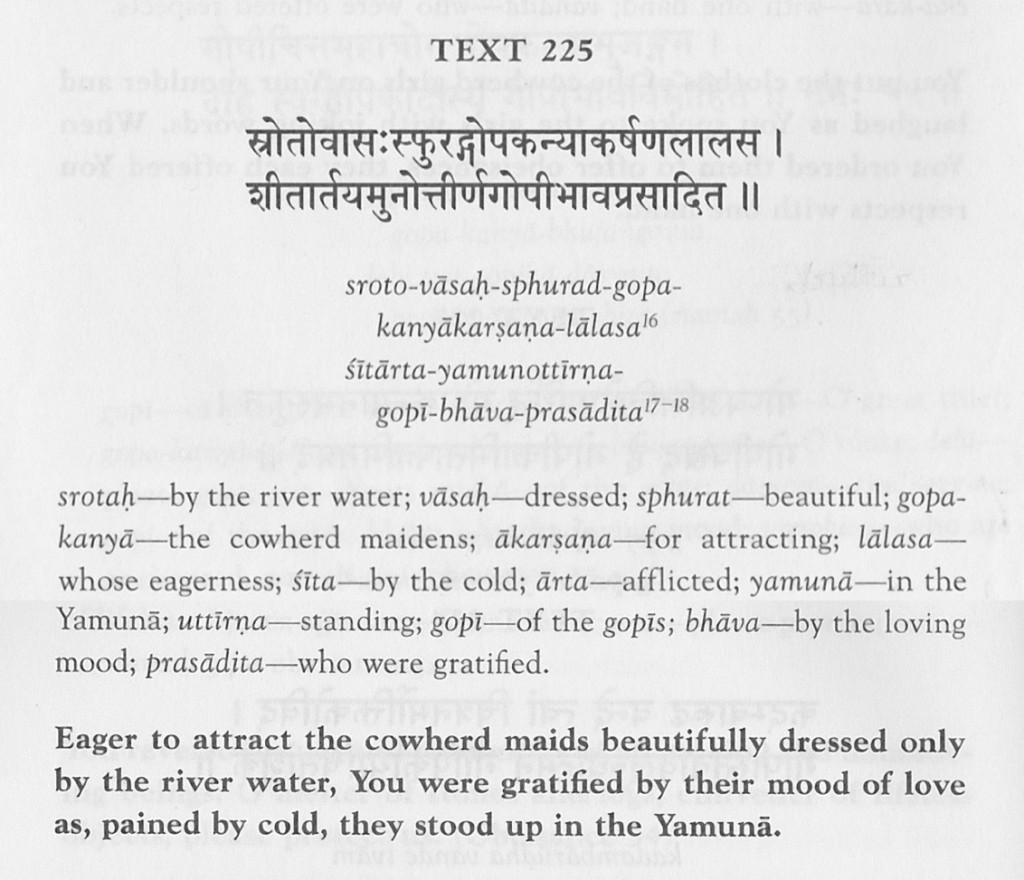

This verse addresses Kṛṣṇa by two sacred names:

sroto-vāsaḥ-sphurad-gopa-kanyā-ākarṣana-lālasa: You who posses an ardent desire (lālasa) to attract (ākarṣana) the gopīs (gopa-kanyā), whose radiant and revealing (sphurat) garb (vāsaḥ) is made of flowing water (srotaḥ). The word sphurat used here has multiple meanings, and almost all of them apply. Sphurat is formed from √sphur, which bears all these meanings: to shiver, to shake, to glitter, to flash, to shine, to break forth, to be revealed. The gopīs, garbed only in moving water, are shivering from cold, and the flowing water also shakes; as it does, it gleams and glitters in the sun. This spangled, sparking flowing dress reveals to Kṛṣṇa, in flashes, the beauty of the gopī’s forms. We should also take special note of ākarṣana, to attract: it contains Kṛṣṇa’s name, being derived from √kṛṣ, to attract, prefaced with ā. (ā+√kṛṣ = attract or pull to.)

śitārta-yamunā-uttīrṇa-gopī-bhāva-prasādita: You who are gratified (prasādita) by the loving mood (bhāva) of the gopīs, who stand up (uttīrṇa) in the Yamunā (or emerge from the Yamunā), suffering (ārta) from cold (śita).

The gopīs, drawn by Kṛṣṇa the all-attractive, forego their natural modesty to rise from the water and wade toward Kṛṣṇa. Satisfied, Kṛṣṇa prepares to negotiate further with them over the return of their clothing, aiming to continue drawing out and intensifying gopī–bhāva, their ecstatic love for Him. (The compound gopī–bhāva will reappear in text 228.)

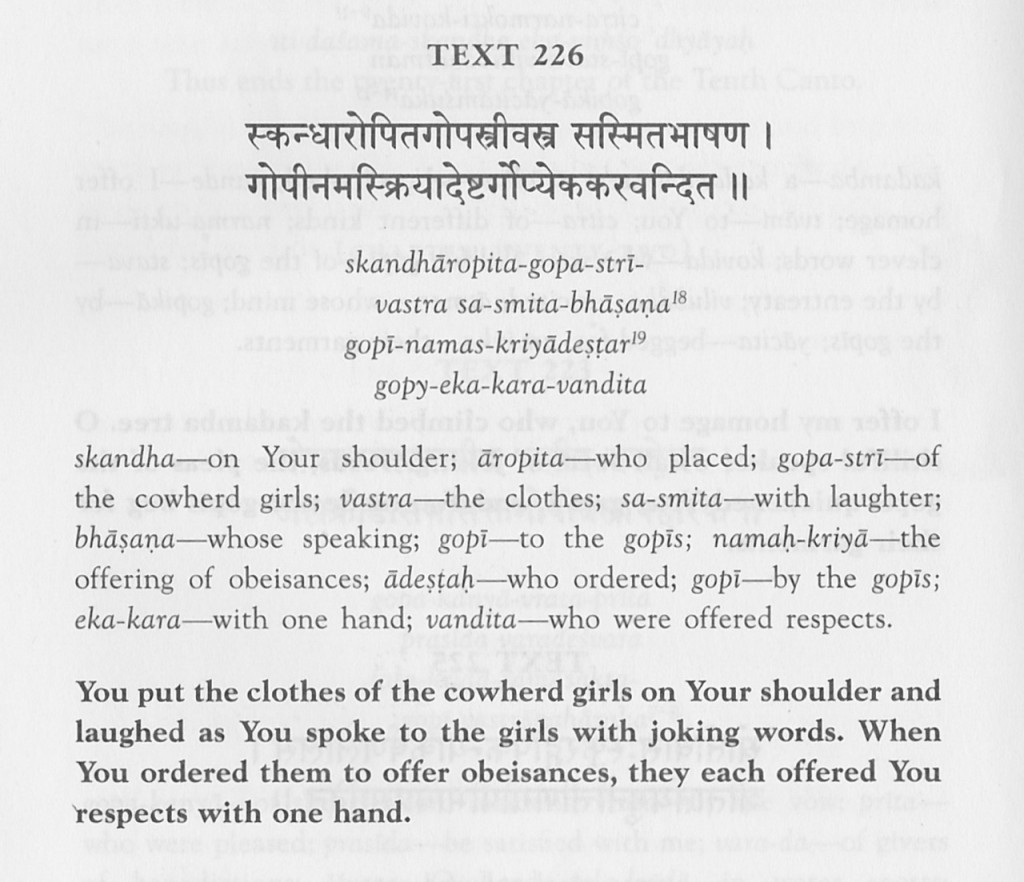

skandha-āropita-gopa-strī-vastra: You who have the clothing (vastra) of the cowherd girls (gopa-strī) deposited (āropita) on your shoulder (skandha). Earlier, their garments were piled on the tree limb. Now, they have been scooped up and placed even more securely in possession of the thief.

sa-smita-bhāṣaṇa: You who speak (bhāsaṇa) with laughter or a smile (sa-smita), or with humorous words.

gopī-namaḥ-kriyā-ādeṣṭaḥ: You who order (ādeṣṭaḥ) the offering of respect (namaḥ-kriyā) by the gopīs. In the Bhāgavatam, Kṛṣṇa tells the gopīs that because they bathed naked, they were guilty of deva-helanam, offending some (unnamed) deva or devas. Commentators suggest Varuṇa or Narāyaṇa, or both, but here, Sanātana Gosvāmī addresses Kṛṣṇa (who is after all sarva-deva-maya) as the one so honored:

gopī-eka-kara-vandita: You who are paid respect (vandita) one-handedly (eka-kara) by the gopīs. At first, the gopīs try with at least one hand to preserve some modesty. But then:

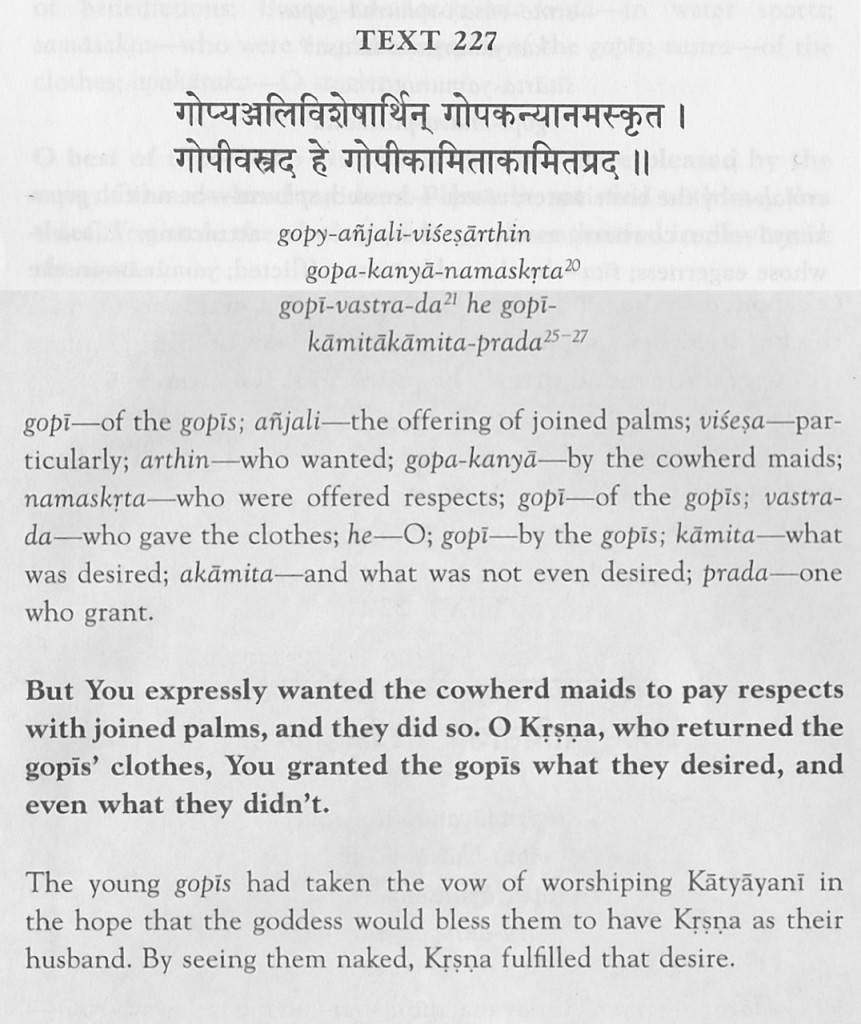

gopī-añjali-viśeṣa-arthin: You who want (arthin) quite particularly (viśeṣa) honor paid properly, with palms of both hands joined and raised to the forehead (añjali), by the gopīs.

gopa-kanyā-namaskṛta: You who receive proper obeisance (namaskṛta) by the daughters of the cowherdmen (gopa-kanyā).

gopī-vastra-da: O giver (da) of clothing (vastra) back to the gopīs.

he gopī-kāmita-akāmita-prada: O bestower (prada) of even what was not desired (akāmita) together with what was desired (kāmita) by the gopīs. akāmita-prada suggests that when Kṛṣṇa answers prayers of the devotees, what ḥe gives is beyond our imaginations and expectations.

Now Sanātana Gosvāmī concludes his recollection of this līla:

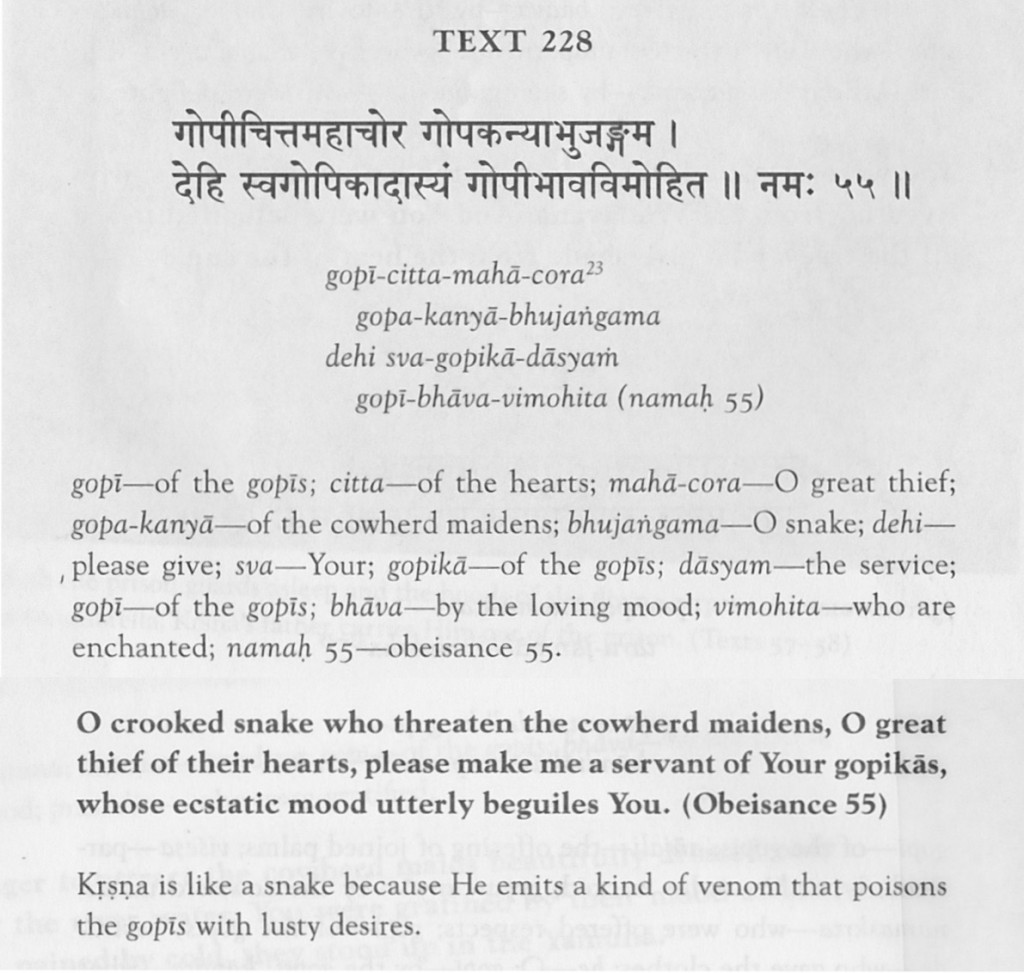

gopī-citta-mahā-cora: O great thief (mahā-cora) of the hearts (citta) of the gopīs. The great thief plundered far more than the gopī’s clothes or their modesty: he stole their hearts. The Bhāgavatam reports that even wearing their restored garments, the gopīs stood stunned into immobility (no celuḥ) their hearts still seized (gṛhīta-cittā) and in Kṛṣṇa’s possession.

gopa-kanyā-bhujaṅgama: O serpent (bhujaṅgama) to (or for) the cowherd’s daughters (gopa-kanyā) Gopīparāṇadhana dāsa translates this as: “O crooked snake who threaten the cowherd maidens,” and notes “Kṛṣṇa is like a snake because He emits a kind of venom that poisons the gopīs with lusty desires.” This word for snake is formed from bhuja, which indicates something curved or bending (and can by itself denote a limb, an arm, or an elephant’s trunk), and the word ga, signifying motion. The snake is something that “moves in curves.” The word here invokes the image of Kṛṣṇa’s graceful form reposing sinuously in the kadamba boughs, like a large black snake.

Now Sanātana Gosvāmī interjects his own prayer into the narrative:

Dehi, he prays: “O grant me,” sva-gopikā-dāsyam, the servitorship (dāsyam) of Your own gopīs (sva–gopikā).

“Please make me a servant of Your gopikās,” Sanātana Gosvāmī beseeches Kṛṣṇa, addressing Him as gopī-bhāva-vimohita: One enchanted (vimohita) by the loving mood (bhāva) of the gopīs.

At the beginning of this narration, Sanātana Gosvāmī asked Kṛṣṇa to bless him (prasīda), addressing Him as Lord of all who give blessings (varadeśvara.) Here, at the conclusion, his request gets restated in explicit form. He asks to become a servant of those gopīs, dehi sva-gopikā-dāsyam. Here we see an expression of his own pure ardent desire, rooted in the profound humility of his heart, exemplary for all Vaiṣṇavas, to become a servant of the servant of Kṛṣṇa.

This request specifically gives voice to Sanātana Gosvāmī’s own eternal identity in Kṛṣṇa’s vraja-līla, that of a mañjarī.

Mañjarīs are a class of gopīs inclined by spiritual disposition to serve in Kṛṣṇa’s conjugal mādhurya-līlā by attending upon other gopīs, or sahkīs, who enter into direct union with the Lord. As expressions of their inclination, or bhāva, the mañjarīs manifest spiritual forms like those of pubescent or near-pubescent girls—younger than the sahkīs whom they serve. The spiritual feelings of the mañjaris are notably for exceptional sweetness and tenderness, profound humility, and ardent longing intensified by a strong sense of separation. Their spiritual ecstasies are not at all diminished by the apparently vicarious nature of their participation in Kṛṣṇa’s līlā—quite the opposite. Such feelings are expressed in Śrī Kṛṣṇa Līlā Stava.

We learn from Bhagavad-gītā that Kṛṣṇa descends with his eternal associates and displays his most confidential vraja-līlā only once in a day of Brahmā. Because none but rare souls of exceptional purity can access this disclosure, Kṛṣṇa kindly descended once more, later in the same yuga-cycle. This time, however, He appears in the form of a devotee (bhakta-rūpa), and the same eternal associates appear with him, similarly arrayed. Together they practice and propagate the appropriate means—combining exceptional accessibility and exceptional potency—by which people even of this age—you and me—can become qualified for admittance into vraja–līlā.

When Kṛṣṇa descended again, just 528 years ago, as the devotee Caitanya Mahāprabhu, six among the mañjarīs who accompanied him took the forms of highly renounced and learned sages who were exemplary practitioners and teachers of saṁkīrtana–yajña. Sanātana Gosvāmī was the senior-most among these Six Gosvāmīs.

As a consequence of their activities, Mahāprabhu’s saṁkīrtana is now spread throughout the earth, and now those of us unqualified by birth and culture can access the work of Sanātana Gosvāmī, who has poured out the feeling of his heart and given it the title of Śrī Kṛṣṇa Līlā Stava.

Sanātana Gosvāmī is very merciful, and so I end appropriately by sharing with you a tribute to his mercy by another member of the Six Gosvāmīs, Raghunātha dāsa Gosvāmī, who relates his own reception of the kindness of Sanātana Gosvāmī. In describing it, Raghunātha dāsa Gosvāmī also employs the metaphor of a drink or elixir. His homage to his master opens with a description of that elixir: the juice or nectar (rasam) made of devotion (bhakti) compounded with (yug) renunciation (vairāgya):

vairāgya-yug-bhakti-rasaṃ prayatnair apāyayan mām anabhīpsum andham

kṛpāmbudhir yaḥ para-duḥkha-duḥkhī sanātanas taṃ prabhum āśrayāmi

vairāgya—with renunciation; yug—endowed; bhakti—of devotional service; rasam— the nectar; prayatnaiḥ—with great effort; apāyayan—made to drink; mām—me; anabhīpsum—unwilling; andham—blind; kṛpā—of mercy; ambudhiḥ—an ocean; yaḥ—who; para—of others; duḥkha—by the unhappiness; duḥkhī—unhappy; sanātanaḥ—Sanātana Gosvāmī; tam—of him; prabhum—the master; āśrayami—I take shelter.

The nectar made of bhakti blended with renunciation: I was made to drink it, I who was blind and unwilling. With unceasing effort he made me drink—he, whose mercy is oceanic, who suffers at the sufferings of others. Of him, of my master Sanātana, I take full shelter.

Śrī Kṛṣṇa Līlā Stava not only reveals the internal spiritual life of its author, but also the external spiritual actions that accompany it, outward acts that expresses and intensifies the internal. The work is more than a poem; it is a performance in perfect devotion.

At the end of text 238, for example, we find “(namaḥ 55).” This marker, and the others like it, reveal the part this work played in the author’s own devotions: “namaḥ” directs him to pay obeisance to Kṛṣṇa after the recitation of this verse; it is the fifty-fifth of such acts out of one hundred and eight, spaced throughout the work. In the very first verse, Sanātana Gosvāmī announces that he has composed this concise summary (sūtram) of the narration of Kṛṣṇa’s pastimes (śri-kṛṣṇasya kathā) for the bliss (ānanda) of offering 108 obeisances (praṇama). This condensation of Kṛṣṇa-līlā, following the sequence in the Bhāgavatam, facilitates the practitioner’s ability to hold firmly in memory the entire narration, and to regularly recollect it and savor it by reciting the sūtras, punctuated by offering 108 praṇamas.

The word sūtra, used by Sanātana Gosvāmī to denote his verses, has particular significance. Sūtra means “thread,” as in a thread of pearls or gems—or texts. Precious stones threaded into a necklace, are small, exquisitely crafted, artfully arranged, and of immense value. Their literary analogues are a class of Sanskrit texts similarly devised to be elegantly formed, highly concise, and conveying great meaning. īn works such as the Vedānta-sūtra (or Brahma-sutra) of Veda-vyāsa, an immense body of learning had thus been meticulously studied, assimilated, condensed, and methodically organized.

Sūtras especially enable memorization (a faculty highly cultivated in ancient times, rapidly perishing in modern). Sutras naturally required unpacking by means of commentaries, and Śrīmad Bhāgavatam itself is Vyāsadeva’s commentary on his own Vedānta-sūtra. (So Śrī Caitanya informed the Vedāntists at Benaras, quoting the Garuḍa Pūrāna). And now the very heart of that Bhāgavatam is again expressed in sūtras, in Sanātana Gosvāmī highly accessible and enchanting sūtra’s—who offers us that most confidential part of Śrīmad Bhāgavatam, as he himself, the best of guides, has relished it.

No Comments