09 Mar Entering Kṛṣṇa-Līlā – Part 1

Courtesy of Śrīla Sanātana Gosvāmī and Śrī Gopīparāṇadhana Prabhu

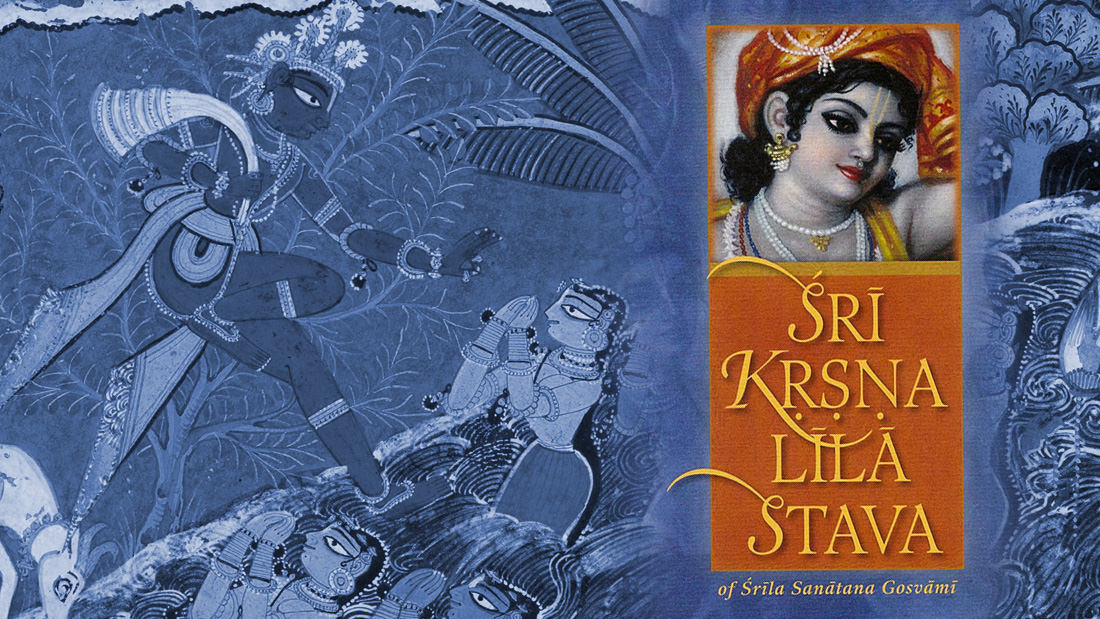

It has been seven years since Sanātana Gosvāmī’s Śrī Kṛṣṇa Līlā Stava, translated with commentary by Gopīparāṇadhana dāsa, came to us via The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, Northern Europe division. The worn and taped dust jack of my copy and its many similarly treated pages testify to my repeated immersions in this book, which unfailingly offers up further riches with each reading.

In short, Śrī Kṛṣṇa Līlā Stava is an extraordinary book. A spiritual as well as a literary masterpiece, this finely wrought work directly conveys to the keen reader the blessings of its great devotee author, who not only opens up for us a path into the Vṛndāvana-līlā of Śrī Kṛṣṇa but also makes himself our companion on the way.

Not everyone, however, is able to appreciate it. A devotee acquaintance, catching sight of my book on an end-table, picked it up and leafed rapidly through a dozen or so pages, apparently just skimming the bold-face English translations of the verses—and ignoring completely the accompanying Sanskrit (given in both Devanāgarī and Roman script transliteration), as well as the word-for-word breakdown. Quickly done, he looked up, plopped the book down with a shrug, and said: “That’s the trouble with this kind of thing! It’s just the same stuff, over and over.”

Gobsmacked—only the UK slangword conveys my condition as I stood there, robbed of speech and motion as my friend turned and quit the room, leaving me alone and wondering over the gulf between his and my reception of the work.

Taking up the offending book, I tried to replicate my friend’s way of reading. I let my eyes run down the pages, skipping from one bold-faced verse translation to the next. I saw the problem right away.

That kind of reading will not do. It is natural enough, being the usual way we size up a potential read on a library or bookstore shelf—or on Amazon (where you can tap your way through the first pages of a possible purchase).

And, I confess, I subjected Śrī Kṛṣṇa Līlā Stava to the same sort of treatment when it first came into my hands. But almost immediately I saw the fault of it. And it is a grave fault, a fault that dooms lives.

Learning how to read Sanātana Gosvāmī’s book, giving it all due attention, endows the fortunate reader with a life-saving ability, a honed skill in rescue and recovery for the soul. This is the epitome of remedial reading—bhavauṣadha, a cure for the affliction of material existence.

In his preface to Śrī Kṛṣṇa Līlā Stava, Gopīparāṇadhana dāsa immediately alerts the reader to the treasure hidden in this book:

This offering of praise in 432 verses is a glimpse into the author’s heart ....

Sacīnandana Swami echoes this observation in his foreword and appreciates the verses as “vivid and colorful pastime pictures, well suited for the relishing of Lord Kṛṣṇa’s sweetness ….”

Accessing the mysteries of Śrī Kṛṣṇa Līlā Stava begins with giving full regard to the original Sanskrit language of the texts. The work is an exemplary instance of the sophisticated poetic art of a high culture, and as such, it realizes that astounding concentrated expression of beauty and sense and feeling that characterizes poetry at its best. The language of such works is often formidably difficult, but here we find the opposite. The Sanskrit is highly accessible.

This is because Sanātana Gosvāmī has employed to great advantage two elements that renders the language, especially in the matter of grammar, quite simple. This tactic well serves his aim: to distill and condense the narration of Kṛṣṇa’s Vṛndāvana-līlā, as recounted in the first forty-five chapters of the Tenth Canto of Śrīmad Bhāgavatam, into a refined, concentrated, and easy-to-consume elixir.

In the process of intensifying the sweet taste of the recounting of Kṛṣṇa’s pastimes, Sanātana Gosvāmī refashions them all into his personal heartfelt hymns of direct address and offerings of homage. As a result, the reader is enabled to savor Kṛṣṇa-līlā enriched by Sanātana Gosvāmī’s own appreciations of it, seasoned, as it were, by a precious, transcendent condiment. Śrī Kṛṣṇa Līlā Stava is thus the literary form of mahā-mahā-prasāda.

The narration, with singular elegance, has been refashioned into a kind of devotional performance, a formal practice or sādhana, and its privileged reader is enlisted into rehearsing it together with the author, who has employed all his mastery of language in service both to Kṛṣṇa and the reader. That service: to transfigure and transport the reader from idle bystander to spirited player in Kṛṣṇa’s Vṛndāvana-līlā.

As readers, we need to take full advantage of the author’s two simplifying devices: First, the wholesale use of the classical Sanskrit compound. Second, the almost exclusive reliance on two grammatical indicators of devotional action: the vocative, indicating calling out to or addressing someone, and the dative, indicated giving or offering something to someone.

Let me note (parenthetically) that ISKCON gets credit for making the vocative famous, having become illustrious even in the halls of academia. Here, from Devavāṇīpraveśikā: An Introduction to the Sanskrit Language, an excellent textbook by Robert and Sally Goldman, we find this example provided to Sanskrit beginners (3rd edition, p. 61) to illustrate the use of the vocative:

Thus, even novice chanters of the Hare Kṛṣṇa mahā-mantra—whose knowledge of Sanskrit may include no more than three words—are already receiving some preparation for Śrī Kṛṣṇa Līlā Stava. In fact, it is evident that the mahā-mantra itself has served as the inspiration, model, and template for that work. Śrī Kṛṣṇa Līlā Stava, by recasting Śrīmad Bhāgavatam in the image of the mahā-mantra, discloses to the attentive reader the treasure-trove inherent in the chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa, and the work thus enriches and enlivens the practitioner’s own nāma-japa and nāma-kīrtana.

Before going any further, let me make clear that my own knowledge of Sanskrit is elementary. I studied the language in a one-semester university course (designed to give students of Indo-European linguistic an overview), but after that, full engagement in ISKCON and my own mental challenges in the matter of languages combined to retard much progress. Still, I can read Devanāgarī, I have a smattering of grammar and vocabulary, I can look up things in Sanskrit-English dictionaries and in some grammar books. Dear reader, I hope my own lack of expertise will serve as a testament to the accessibility of Sanātana Gosvāmī’s great work, and encourage everyone, at whatever level of Sanskrit learning, to engage with the original text.

Here I’ll go over some verses from Śrī Kṛṣṇa Līlā Stava in order demonstrate the process of reading them, taking advantage of the kind work of Gopīparāṇadhana Prabhu.

The verses I’ve selected are special, for in them the author’s feelings become most nakedly expressed.

This is how Text 223 appears on the page:

We assume that the reader is already acquainted with this pastime, whether through reading the twenty-second chapter of Śrīmad Bhāgavatam Tenth Canto or the chapter of the same number in Śrīla Prabhupāda’s English prose retelling, Kṛṣṇa, The Supreme Personality of Godhead. (As you can see in the scan above, Gopīparāṇadhana dāsa has inserted superscript numbers within the transliterated verses; these numbers indicate the tenth-canto verses corresponding to Sanātana Gosvāmī’s own narration.)

The first line here demonstrates the author’s typical use of the Sanskrit compound:

gopa-kanyā-vrata-prīta

The whole line is actually a single noun, constructed according to the rules of the Sanskrit compound—hitching together four words (or really five, because gopa itself is a compound of go + pa, cow-protector). Within the body of the compound, the changeable word-endings that signify grammatical case—“inflection”—are dropped for every word save the last. Only the final word is, as they say, “inflected.” That last word, prīta, “pleased,” is here in the vocative, thus addressing Kṛṣṇa as “one who is pleased,” or “O you are pleased . . . .”

The standard way of reading a Sanskrit compound is to proceed from right to left: Here we start with the subject, Kṛṣṇa, “he who is pleased,” prīta. Pleased by what? The next word to the left, vrata, answers that question: Pleased by a vow. By whose vow? The vow of the unmarried daughters, kanyā, “maidens” on the verge of puberty. Whose daughters? The herdsmen, gopa, protectors of the cows. All four words couple together, like boxcars in a train, to become a name of Krishna: gopa–kanyā–vrata–prīta, “He who is pleased by the vrata (vow) of the cowherds’ daughters.”

“Vow” does not adequately translate the word vrata, although making a vow forms an important part of a vrata. A vrata, in the full sense, is a prescribed ritualistic undertaking, usually of some difficulty, which one commits to and fulfills under a solemn vow, with the aim of achieving a (usually) pious end. It is a “meritorious act of devotion or austerity” (Monier-Williams). The gopī–vrata honored the standard practice of unmarried girls to satisfy the goddess Katyāyani, so that they may be given in marriage to a desirable husband.

As recounted in first six verses of this chapter, the gopīs, having reached the appropriate age, carefully performed the katyāyani–vrata, each longing for none but Kṛṣṇa as bridegroom. Their devotion captured Kṛṣṇa’s heart.

From this, Sanātana Gosvāmī has crafted a name of Kṛṣṇa, gopa–kanyā–vrata–prīta, and here he is addressing the Lord by that name. Such compound names of Kṛṣṇa are many, and often devotees are initiated into devotional service with them. For example, the initiated name of our translator, gopī–parāṇa–dhana–dāsa, means he who is the servant (dāsa) of the one—i.e., Kṛṣṇa—who is the treasure (dhana) of the life or vital air (parāṇa, a variant of prāṇa) of the gopīs. (The divine name Gopīparāṇadhana dāsa appears in song of Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Thākura in his collection titled Śri Nāma-kīrtana.)

When we turn to the full verse translation (given in bold type), we find the holy name gopa–kanyā–vrata–prīta rendered into English by a complete sentence: “You were pleased by the vow of the cowherd maidens.” The meaning is simply and lucidly conveyed in standard English, but we notice at once how the concentrated expressive power of the Sanskrit poetry has become unavoidably diluted, and the vocative sense is lost.

It is well known that poetry as such defies translation. Language is poetic when as many of its elements as possible are used to produce the aesthetic effect. The sound and rhythm of the words are as vital as their lexical meanings, and all forms of literary special effects and word play are granted their field day. The inspired poetry or kavya of ancient and medieval Sanskrit is especially proof against efforts to being replicated in modern English. Therefore, in his translations Śrīla Prabhupāda has supplied his readers with the materials we need to access the original—the original language, the word-for-word meanings, the text translation, and the purport. Gopīparāṇadhana Prabhu has wisely followed in his footsteps.

Opting for clarity and directness in his verse translations, Gopīparāṇadhana dāsa knows that they are only one element toward a deeper realization of the text through the original language. And in Śrī Kṛṣṇa Līlā Stava, direct, unmediated access to the original language become feasible for us, because of Sanātana Gosvāmī’s use of the simple and simplifying device of the compound. Taking additional help from Gopīparāṇadhana dāsa’s work, any of us, with a little effort, can learn to read the Sanskrit texts directly, that is, without any need for a mental translation.

Looking at each verse on the page, we can easily and conveniently direct our attention as needed, weaving our way back and forth among the original Sanskrit text, the appropriate word-for-word rendering, and the full verse translation. Soon, even if our memory power has been much vitiated by modern life, we can read the Sanskrit directly. This will prove to be worth the effort. A translation inevitably dilutes the concentrated expressive power of the Sanskrit poetry. Moreover, in this particular case, direct reading brings us some way toward an immediate experience or realization of the transcendent unity of Kṛṣṇa, whose names, forms, activities, abodes, associates, and descriptions, are, each and every one, a vessel that contains the whole.

The second pada (or half-line) of the verse is: prasīda varadeśvara. This utterance is an interjection into the Bhāgavatam narrative by Sanātana Gosvāmī. He directly pleads to Kṛṣṇa, prasīda, formed from the root pra-√sad, means “be merciful” or “be gracious.” He means, “Be merciful to me!” And he addresses Kṛṣṇa as the īśvara, the Lord or the master. Of what or whom? Of vara–da, all those who give (da) blessings (vara). We have just heard in the previous line Kṛṣṇa extolled as one pleased by the vrata of the gopīs, undertaken to obtain the blessings of gaining Kṛṣṇa as their husband. In other words, they asked Kṛṣṇa to give them Kṛṣṇa. Here Sanātana Gosvāmī himself joins in their prayer. He shows his hopefulness by addressing Kṛṣṇa as the best and greatest of all who give blessings. The greatest giver would have to be the greatest both in the liberality of his giving and in the value of his gifts. Kṛṣṇa is both. Sanātana Gosvāmī’s plea here, at the outset of this episode, anticipates his full articulation of it five verses later (228).

The second line of Text 223 forms a single compound:

jala-krīḍā-samāsakta-gopī-vastrāpahāraka

We follow the same left-to-right procedure to read this compound. In transliteration, however, the final two words of the compound are not separated by a hyphen; rather the final vowel of vastra and the initial vowel of apahāraka merge to form an ā. a + a = ā. Here we encounter the most simple instance of the Sanskrit grammatical feature called sandhi, “euphonic junction” or “combination.” In their introductory grammar, the Goldmans introduces the topic of sandhi like this:

Perhaps the most peculiar, and initially dismaying, feature of Sanskrit is it complex system of conditional phonological change known as [given in devanagari here] (sandhi), or combination. Various kinds of environmentally conditioned changes occur in all languages, but no other has for formalized and systematized them as has Sanskrit.

But here, there is no need for dismay on our part, for Gopīparāṇadhana dāsa, following the practice of Śrīla Prabhupāda, undoes all the sandhi between words in the compound (“external sandhi”) in the word-for-word meaning section. Thus, vastrāpahāraka is broken down there as “vastra—of the clothes” and “apahaāraka—O stealer.” Reading the compound from right to left we get: “O stealer of the clothes of the gopīs who were engrossed (intensely absorbed) in water sports.”

In the verse translation, Gopīparāṇadhana Prabhu renders this one compounded word into a complete English sentence: “You thief, You stole the clothes of the gopīs engrossed in playing in the water!” (Here, our translator shows us the tone of mock reproach—a blend of pleasure and indignation—expressed in the gopī’s response.) Making good use of the all facilities provided by Sanātana Gosvāmī and Gopīparāṇadhana Prabhu, we should quickly be able to savor the intense taste contained in the original language.

No Comments