23 Jun How I Spent My Spring

After retiring from the GBC in 2014, I began to miss Europe and the devotees in Europe. I had had many occasions to associate with both in the course of my service, especially after I was assigned oversight there in 2000. So when the opportunity recently arose to return, I was eager to do so. My enthusiasm was enhanced by the fact that, this time, I could undertake my visit freed from duties of officialdom: I was now not obliged to give patient ear to protracted narrations of problems and shortcomings, nor to take careful note of all those flaws and faults no one had mentioned at all.

This was a different kind of trip. It would be all wheat, no chaff; all milk, no water.

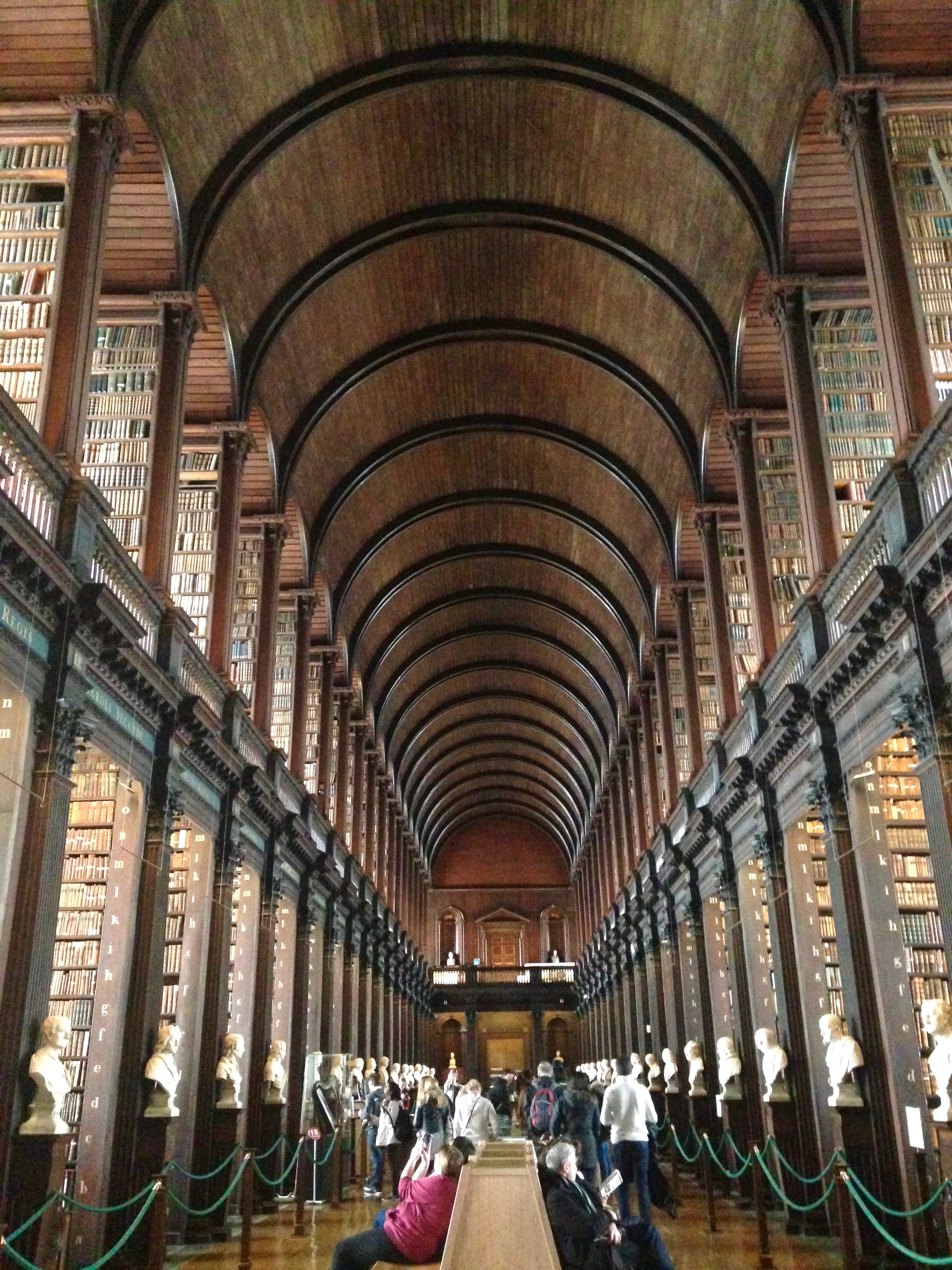

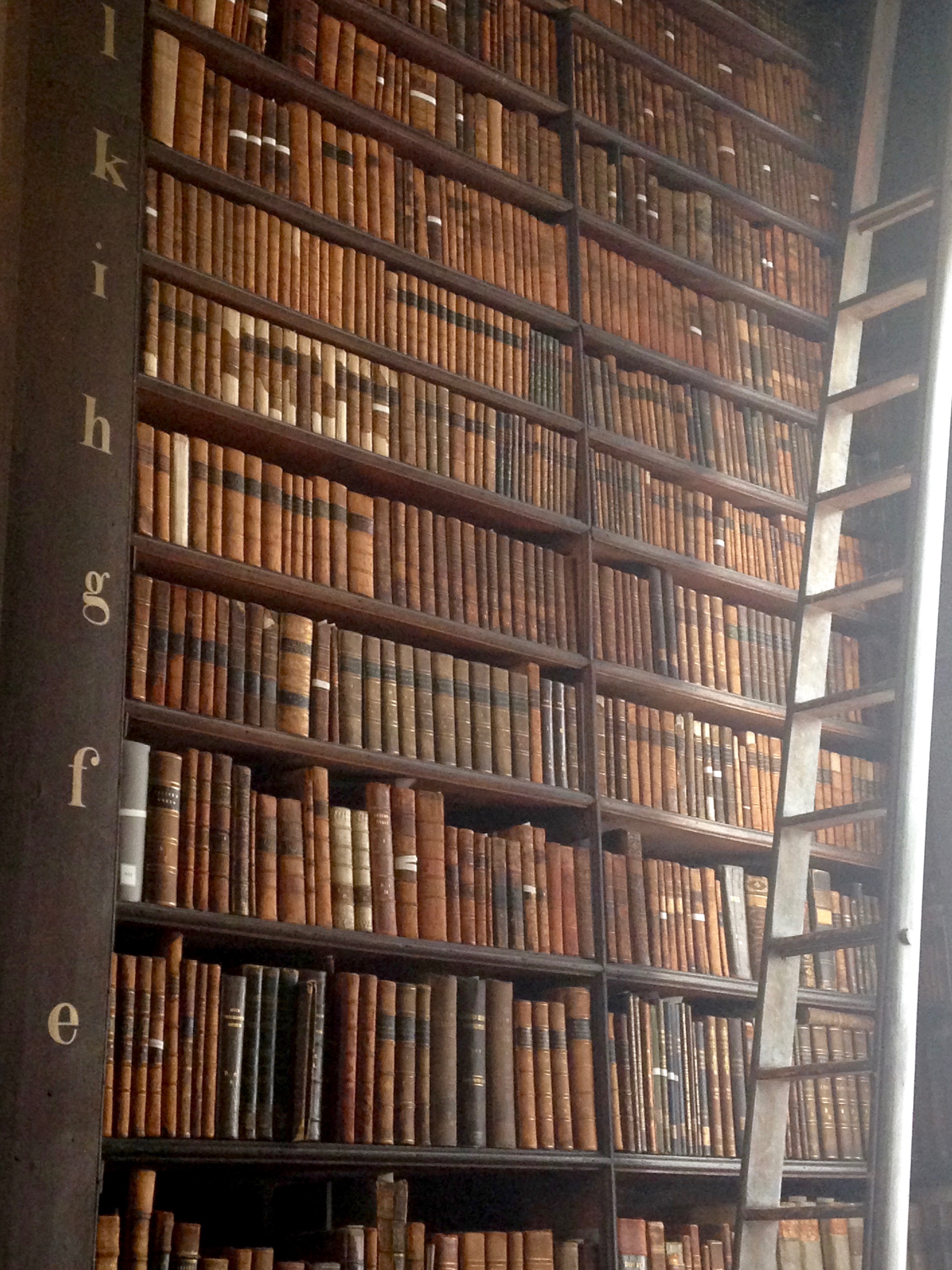

The following pictures (all taken by Śraddhā dd) will record Deities, temples, devotees, and devotional activities, and in addition churches, cathedrals, castles, and the like. I confess that I used to fit in such sightseeing whenever I could during my days as a religious bureaucrat. I have a strong sense of history, and pre-modern Europe—Europe before the so-called “Enlightenment”—with its proliferation of cathedrals, monasteries, and castles, now maintained mainly as relics—interests me as a time when human society of four orders—priests and monks; kings and nobles; non-noble landowners, merchants, and traders; and peasants or serfs—approximated to a system of varṇa and āśrama, and the central, overriding human task of that society was salvation.

What had happened to it? Where had it gone wrong? How do we, in effect, reinstall it? If Christian civilization, after an incubation of 500 years, lasted 2000 years (a thousand up and a thousand down) how do we foster a Gauḍīya-vaiṣṇava civilization to last the predicted 10 millennia, five times as long.

Yet for now, I relish contemplating all those remnants of former glory—for example, the awesome, elaborate, extraordinary, expansive cathedrals, overflowing with colors and shape designed to seize the mind and senses and direct them to God. And I try imagining the forms of life that engendered those cathedrals. It is clear that there was some life of bhakti—a communal effort of engaging the senses in the service of the master of those senses. That way of life had departed, and its passing has been noted and mourned. In the sound of the surf at Dover Beach the poet Matthew Arnold heard the “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar” of the “Sea of Faith.” And, using words that Śrīla Prabhupāda later adapted, William Wordsworth lamented the disappearance of the old culture of “plain living and high thinking.”

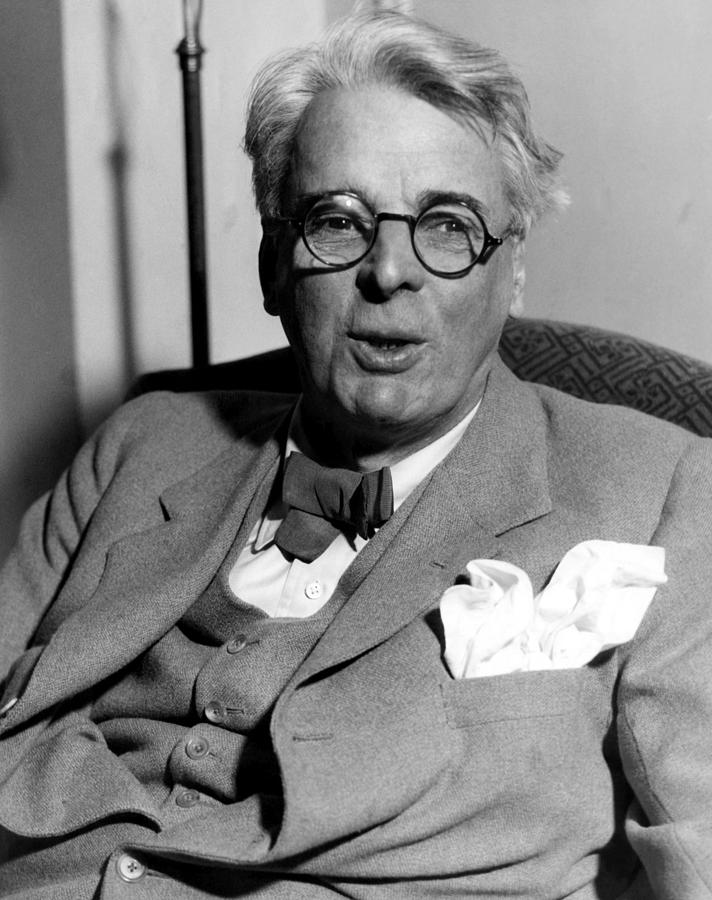

The modern Irish poet William Butler Yeats, remembering what Arnold heard at Dover beach, wrote this little poem:

THE NINETEENTH CENTRY AND AFTER

Though the great song return no more

There’s keen delight in what we have:

The rattle of pebbles on the shore

Under the receding wave.

Those great cathedrals also depict the entire cosmological sacred order or hierarchy, all realms and stations, from top to bottom, together with sacred history, together showing the purpose of human life in the scheme of things. As such, they furnish me with inspiration in my current engagement, the Temple of the Vedic Planetarium in Māyāpura, which elaborately and powerfully sets before our eyes the divine order of the universe. In addition, therefore, those European cathedrals reinforce my conviction that there is only one religion and one purpose to human life.

In another poem, composed in 1919, Yeats gives a powerful, devastatingly accurate, description of our time:

Things fall apart, the center cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

All full of passionate intensity.

The poets may see what is wrong, and feel deeply what is missing. Yet their verses cannot remedy it.

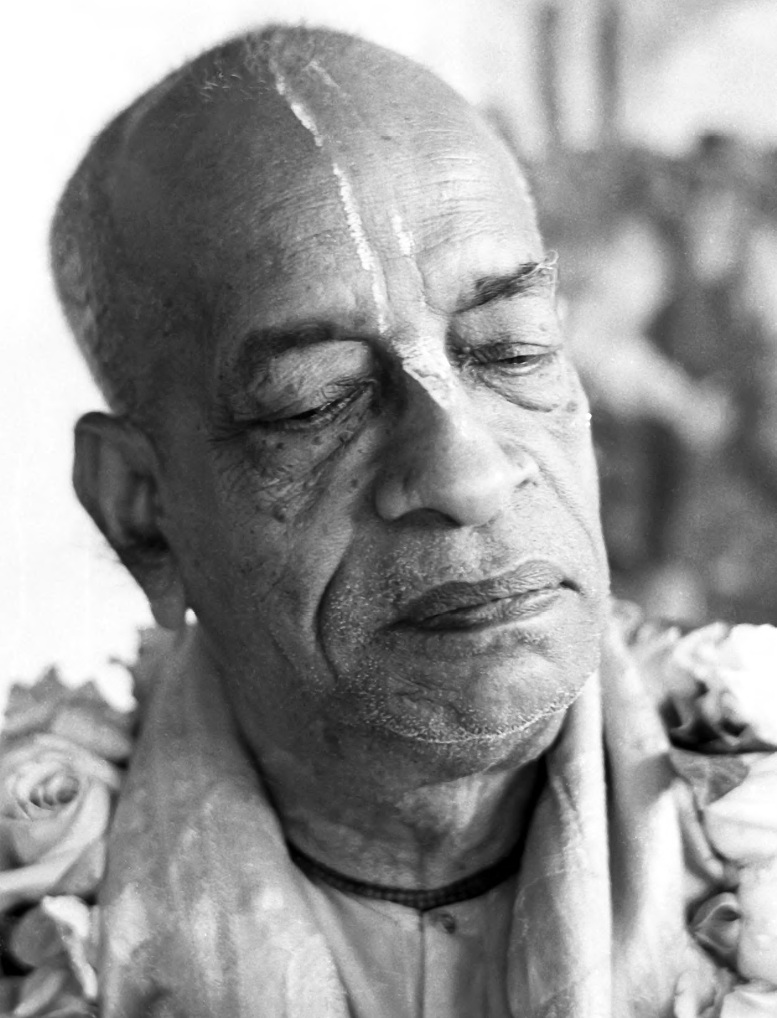

The remedial verses, rather, come from Śrīla Vyāsadeva, whose Śrīmad Bhāgavatam is “directed toward bringing about a revolution in the impious lives of the world’s misdirected civilization” (SB 1.5.11). In his introduction to Śrīmad Bhāgavatam, Śrīla Prabhupāda concludes with this:

We simply request the leaders of all nations to pick up this science of Kṛṣṇa for their own good, for the good of society and for the good of all the world’s people.

Śrīla Prabhupāda has directed us to establish at the world headquarters of his international society at Māyāpura, a temple that is the rendering of the Śrīmad Bhāgavatam in the form of a building—a building that is the cakra, as it were, upon the crown of all ISKCON worldwide. In this way, he will bring about the fulfillment of the purpose of Śrīmad Bhāgavatam, “a cultural presentation for the respiritualization of the entire human society.”

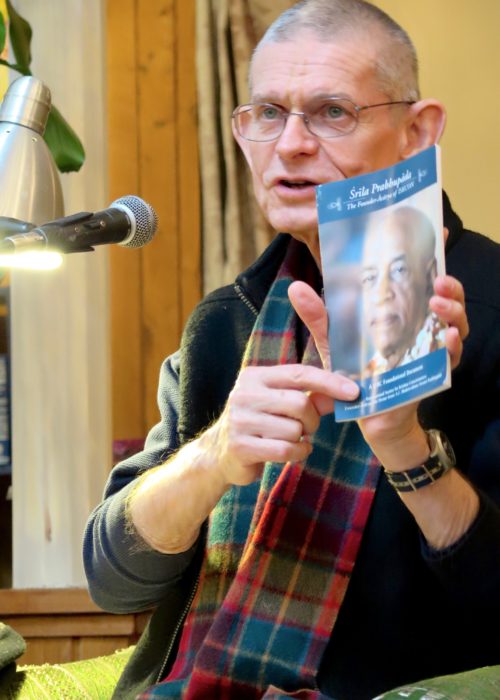

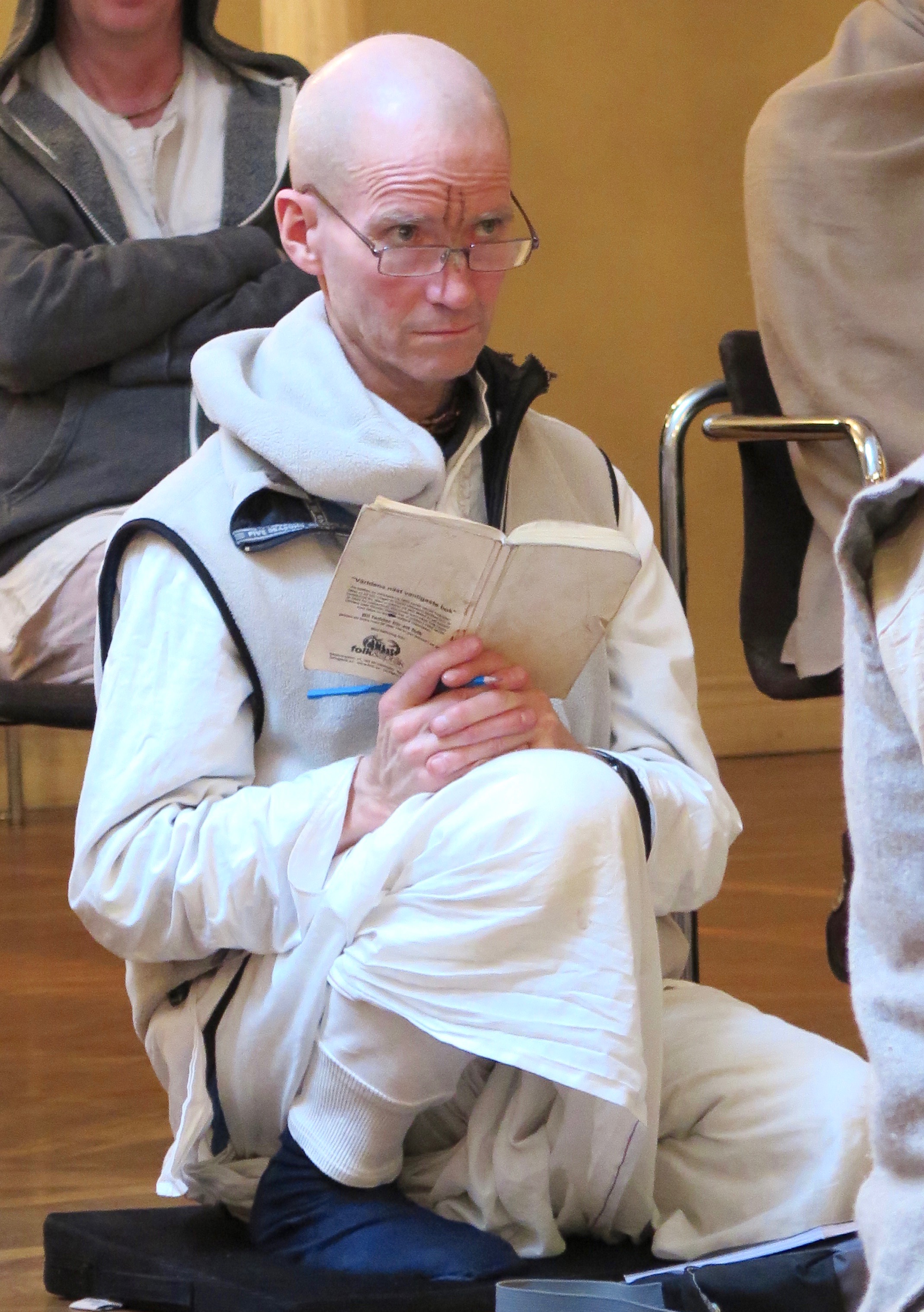

Here are the pictures, memorializing occasions, in the association of devotees for reflecting on past, present, and future:

Visiting a great monument of the Age of Faith: the Milan Cathedral outside.

Some interior cathedral-scapes.

The apostle St. Bartholomew, holding his own skin. (He was martyred by flaying.)

Above the altar: A red light illuminates a nail,

a venerated relic from the cross of Jesus.

In the castle of Sforza, the noble ruling family of Milan.

Mary holds the body of her slain son Jesus, just taken down from the cross:

the last, unfinished work of Michelangelo, the “Pieta Rondanini.”

The view from the ancient upper city of Bergamo:

a fortified, mountain-top city-citadel.

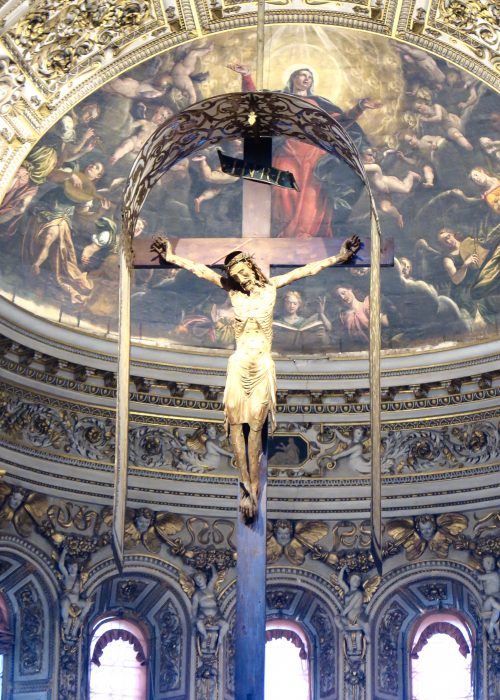

Over the main altar in the Bergamo cathedral.

Two American tourists and their native guide, Madhusevita Prabhu.

Bergamo street art.

Panorama of Florence (Firenze), famous for being near Villa Vrindavan.

The big building is the famous cathedral, background for selfies.

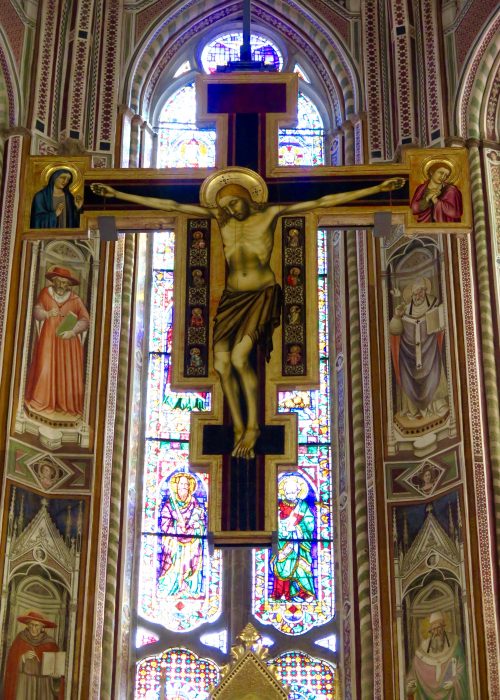

Basilica of Santa Croce (Holy Cross), the largest Franciscan church.

Two outside views of the central cathedral and its famous dome by Brunelleschi, revered by engineers worldwide as a “miracle.”

The cathedral at Siena, the crown of a hill-top city. The cathedral is dedicated to the Virgin Mary, shown here being crowned by Jesus after

her assumption into Heaven.

Interior of the very baroque chapel of the renowned St. Catherine of Siena.

Piazza del Campo of Siena, the large, central plaza of the city. A chocolate festival was in progress there when we visited. The plaza is also well known for the horse races held there twice each summer.

Our guide to Siena was Narada Muni dasa (on the left), born and raised in this very town. On the right is Ratna-bhusana-bhusana dasa, a devotee of Iranian descent from Sweden.

The beautiful Protestant church of St. Peter and Paul, in Weimar. Johan Sebastian Bach—born in the nearby town of Eisenach—had played the organ here. We were fortunate to have tickets to a very fine performance of Bach’s B-minor Mass there. (As it happened, the state of Thuringia was observing a month Bach festival during our visit.) Another famous artwork graces the altar: Cranach’s visionary depiction of the crucifixion of Christ.

In Weimar with Krsnadasa Kaviraja dasa,

a local resident, expert guide, and even better host.

On the heights overlooking Weimar the remains of the Nazi Buchenwald concentration camp. After reflecting on some of the best efforts of humanity in the town, one can take a short drive to reflect on the worst. The motto or warning on the iron entrance gate “Jedem das Seine”—“To each his own” or “you get what is coming to you”—cuts both ways.

Celebrating Gaura-purnima in Berlin. Saudamani dd bathes Gaura Nitai at the Jagannatha Temple there, while Sacinandana Swami leads kirtan.

In Sligo County, Ireland stands the Protestant Church at Drumcliff, very near the large rock formation named Ben Bulben.

Above the altar of Drumcliff church. William Butler Yeat’s

paternal grandfather was rector there.

The grave of Yeats, near the entrance of the church. We find the gravestone epitaph at the end of the poem “Under Ben Bulben”;

Under bare Ben Bulben’s head

In Drumcliff churchyard Yeats is laid,

An ancestor was rector there

Long years ago; a church stands near,

By the road an ancient Cross.

No marble, no conventional phrase,

On limestone quarried near the spot

By his command these words are cut:

Cast a cold eye

On life, on death.

Horseman, pass by!

Maddy Jean-Claude Durr

Posted at 11:18h, 23 JuneTwo journeys for the price of one – the literary philosophy and reflection, and the visual – it feels like I’m there – tourist guide to spiritual Europe. In Bhaktivedanta Swami Gurukula, New Govardhana, Australia (aka Krishna School) the year 9 and 10 students had an exam on the foundation texts of Bhakti – in this case Nectar of Instruction and Sri Isopanisad. Inspired by none other than yourself, the first question of the exam was “Define the term ‘Hierarchy’.” Hierarchy is a sensitive topic in modern society, as somewhere in the dogma of apparent democracy there is a loss of seeing a higher being and a higher purpose. I like this blog entry because it takes us back to a time where a higher dimension was prevalent and it so clearly shows that the populous are progressing to another level of humanity because of it. To see such architecture and art, in comparison to this age of pixels and box buildings, brings a surge of hope; perhaps if we also look to the Lord and pray, then maybe just maybe something beautiful will come out of it.

Kaisori Devi Dasi

Posted at 12:24h, 23 JuneBeautiful!

James Kelley

Posted at 16:55h, 23 JuneThank you.

Gunarnava Sitaram das

Posted at 21:13h, 25 JulyVery wonderful.

yugala-rasa d.d.

Posted at 14:06h, 10 SeptemberThank you Srila Gurudeva,

Sankarsan Das

Posted at 07:04h, 27 MarchI appreciate how you are looking back in history to a time when Europe was very much more spiritually orientated. You then lead us to the conclusion that we have to keep ISKCON from following the same secularization path. May Lord Caitanya protect us!