03 Nov Receiving the Blessing

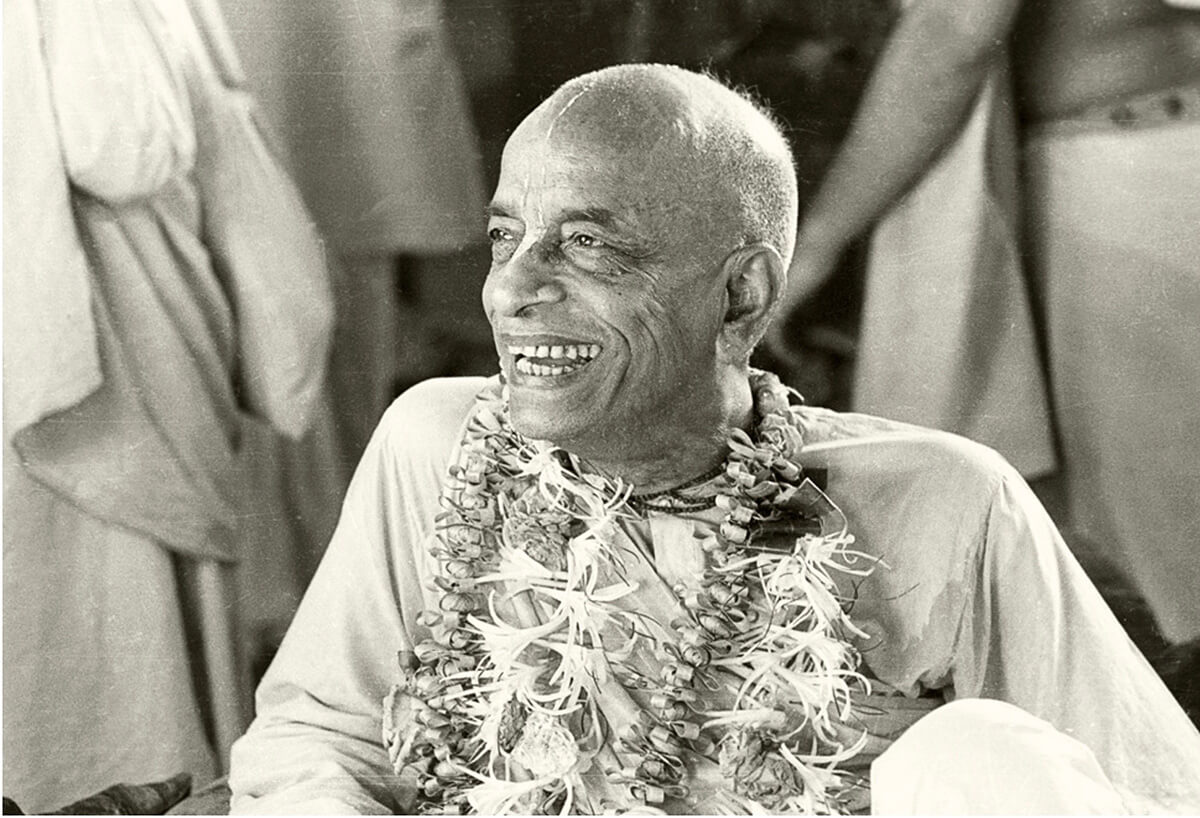

Each morning in ISKCON temples we pay homage to our Founder-Ācārya Śrīla Prabhupāda by singing Śrī Guru-vandanā together while offering him guru-pūjā.

Śrī Guru-vandanā is a Bengali song composed by Śrīla Narottama dāsa Ṭhākura. In the hymn’s second stanza, that great ācārya directs our attention to the words or speech (vākya) issuing from the guru’s lotus-like mouth (guru-mukha-padma). Śrīla Narottama dāsa Ṭhākura

says we should make those words one (aikya) with our hearts and minds (citta). And, he goes on to say, we should allow no other desire or longing (āśā) to reside there.

In the next stanza, Śrīla Narottama dāsa Ṭhākura spells out some consequences of our thus assimilating the words of the spiritual master. Those potent words then confer upon us the gift of spiritual sight (cakhu-dān). Thereupon transcendent knowledge (divya-jñān) illuminates our hearts, and this knowledge obliterates all avidyā and bestows prema-bhakti.

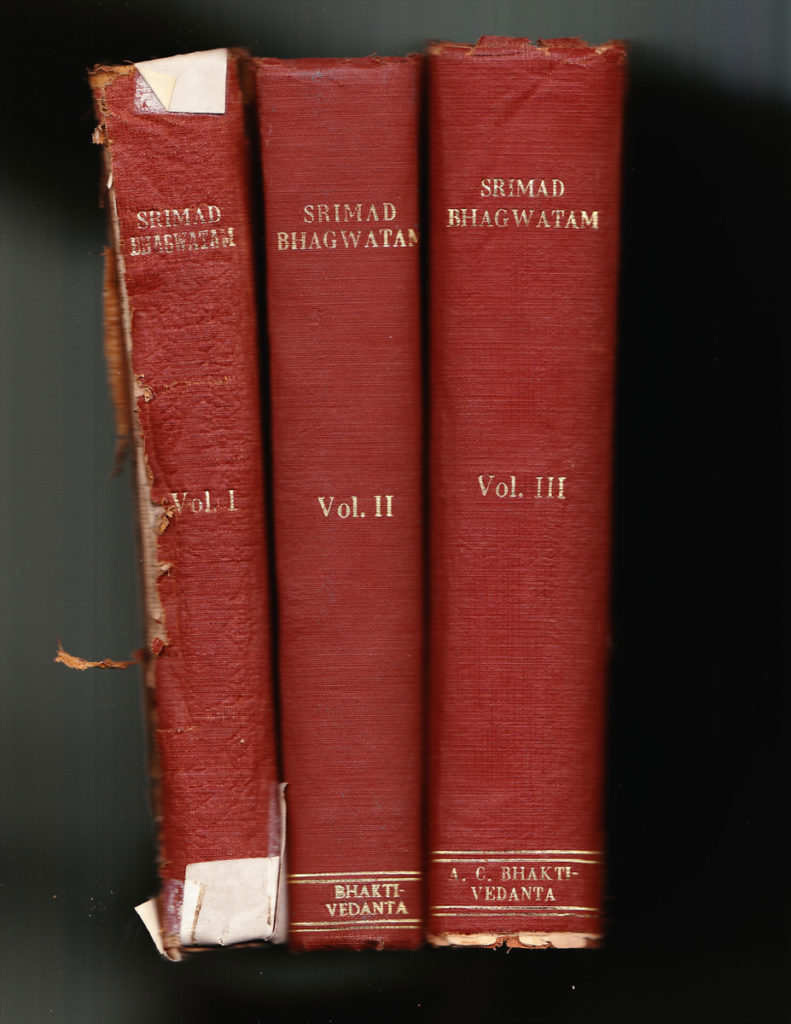

Śrīla Prabhupāda took especial pains to bestow his vākya through the medium of written English and to publish those writings in book form. Prior to embarking from India in 1965 on his solo expedition to the West, Śrīla Prabhupāda, working virtually alone, had composed and published, in three hardback volumes, his English-language translation and commentary on the First Canto of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. He brought boxes of these books with him aboard the Jaladuta, and they accompanied him on the voyage of over 9,000 nautical miles from Calcutta to New York. There he began to gather, organize, and deploy the necessary and spiritual resources—material, human, and spiritual— for their eventual distribution and reception worldwide.

In this way, his guru-vākya itself gave proof to its empowerment to spread over space and time.

In the pages of the very first of these volumes we find one place that Śrīla Prabhupāda most brilliantly elucidates for us the full process of the transmission of that divya-jñān which Śrīla Narottama dāsa Ṭhākura referred to in his song. In Śrīla Prabhupāda’s presentation of the final verse of the third chapter of Canto One, he spells out the conditions necessary for the transmission to take place—namely, the qualifications required in the speaker and in the hearer.

Since our very reading of this particular text and purport is, in itself, an occasion of such transmission, the text is implicitly self-referential, and all the more powerful for that. Still, if the reader is not paying close attention, he or she may be insufficiently present to receive the full benefit.

The speaker of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam 1.3.44 is Sūta Gosvāmī, and it is uttered at the second public recital of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. The hearers on this occasion are the sages gathered at Naimiṣāraṇya forest. The time is the onset of Kali-yuga. They knew that Sūta Gosvāmī had been present at the very first narration of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, which Śukadeva had delivered to the emperor Parīkṣit and others auditors. Now the sages at Naimiṣāraṇya wanted to hear that same narration from Sūta.

Here is Śrīla Prabhupāda’s English rendering of what Sūta had replied to their request:

O learned brāhmaṇas, when Śukadeva Gosvāmī recited Bhāgavatam there (in the presence of Emperor Parīkṣit), I heard him with rapt attention, and thus, by his mercy, I learned the Bhāgavatam from that great and powerful sage. Now I shall try to make you hear the very same thing as I learned it from him and as I have realized it.

Śrīla Prabhupāda opens his commentary on this verse with a sentence that is remarkably terse, highly provocative, and profoundly illuminating:

One can certainly see directly the presence of Lord Śrī Kṛṣṇa in the pages of Bhāgavatam if one has heard it from a self-realized great soul like Śukadeva Gosvāmī.

In a similar way, Kṛṣṇa is directly present in His pictures, or His statues, or in the descriptions or narratives about Him. When it comes to Absolute Truth, the signifier and the signified are one. Accordingly, our reception of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam is completed or fully accomplished when we see Kṛṣṇa directly “in the pages.” The mediation of words, of symbols and signs, dissolves.

Now go back and look at the purport’s first sentence, quoted above. You should notice how Śrīla Prabhupāda has pulled off something that is simultaneously bold and almost subliminal. Like a magician, he has artfully transferred the mode of mediation from the spoken to the printed word. Long ago, Sūta’s audience had been hearing Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam; Śrīla Prabhupāda’s audience now is reading it. In this way, our own immediate reading of Prabhupāda’s presentation of Bhāgavatam is made contiguous and congruent with the hearing of it by Śaunaka from Sūta and by Sūta’s from Śuka.

Thus in one sentence, the paramparā idea of an unbroken lineage of sages, both illuminated and illuminating, is invoked implicitly—thereby linking Śrīla Prabhupāda and his audience together with Sūta and his own. This is melded into the explicit proclamation that successful reception of Bhāgavatam bestows direct perception of Kṛṣṇa.

Here, Śrīla Prabhupāda proclaims what Sūta Gosvāmī meant by his reference to his presenting Bhāgavatam “as I have realized it” (yathā-mati); “realization” means seeing “directly the presence of Lord Śrī Kṛṣṇa in the pages of Bhāgavatam.”

As Śrīla Prabhupāda has repeatedly stressed: Because Kṛṣṇa is absolute, without duality, He is therefore fully present in His name. We find this impressively spelled out in a text from the Padma Purāṇa, quoted in Cc. Madhya 17.133:

nāma cintāmaṇiḥ kṛṣṇaś caitanya-rasa-vigrahaḥ

pūrṇaḥ śuddho nitya-mukto ’bhinnatvān nāma-nāminoḥ

Here it is stated that the name “Kṛṣṇa,” in and of itself, is like a transcendent cintāmaṇi, the celestial gem that fulfills all wishes. The name “Kṛṣṇa” is the very embodiment (vigraha) of all spiritual ecstasies (caitanya-rasa). The name “Kṛṣṇa” is perfect and complete (pūrṇa), free of all contamination (śuddha), and fixed perpetually in transcendence (nitya-mukta).

The final line of the text replies to the readers’ obvious question: “But how can a mere name possess such extraordinary properties?” The answer: Because of the presence of the spiritual condition of non-difference (abhinnatva) between the name (nāma) and the named (nāmin).

In the rest of his purport, Śrīla Prabhupāda goes on to elucidate the conditions necessary for successful transmission—whether a single instance or a sequence—to occur: the speaker and the hearer must each be properly qualified or, as he puts it, “bona fide.”

He deals first with the speaker:

One cannot, however, learn Bhāgavatam from a bogus hired reciter whose aim of life is to earn some money out of such recitation and employ the earning in sex indulgence.

A speaker whose abilities are only those of a dazzling stage actor or performer, and nothing more—“a bogus hired reciter”—is not qualified, no matter how skillfully the audience has become enraptured. That kind of talent is a counterfeit qualification.

The appearance of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam in this way is spurious, a fake, because the motives and aims of such popular entertainers are impure: they narrate kṛṣṇa-līlā only to “earn some money out of such recitation and employ the earning in sex indulgence.”

With this, Śrīla Prabhupāda interjects a stipulation he will return to and develop:

No one can learn Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam who is associated with persons engaged in sex life. That is the secret of learning Bhāgavatam.

There is a requirement of purity for transmission of the knowledge contained in Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, and this requirement constitutes a “secret,” that is, a necessary condition that not everyone will be willing or able to recognize, comply with, or appreciate.

At this point, Śrīla Prabhupāda alerts his readers to another class of unqualified persons who sometimes indulge in writing or speaking about Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam:

Nor can one learn Bhāgavatam from one who interprets the text by his mundane scholarship.

Persons whose proficiencies are only those of a “mundane”—that is, merely academic—scholar may naturally impress us. Yet even though such scholars may have read deeply and skillfully with great attention and retention in many languages, their qualifications to grasp Bhāgavatam remain inadequate. Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam remains a closed book to them as well.

In both cases—the entertainer and the intellectual—the conditions for the manifestation of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam are not fulfilled. It eludes them, still a “secret” veiled from them both.

What is this “secret?” How can we gain access? What does it disclose? The answers proceed:

One has to learn Bhāgavatam from the representative of Śukadeva Gosvāmī, and no one else, if one at all wants to see the presence of Śrī Kṛṣṇa directly in the pages. That is the process, and there is no alternative.

Here, we discover that the “secret” has two aspects: one concerns the form of transmission—the qualified speakers and hearers; the other, the content of transmission: not just the words or signifiers, but that which is named or signified.

We may recollect now that this hidden, esoteric feature of Bhāgavatam had in fact already been announced by Śrīla Prabhupāda in the very first sentence of his purport: to hear from a self-realized great soul, and to see Lord Kṛṣṇa directly in the pages of Bhāgavatam. The bold, prominent placement of this proclamation in the purport is significant: although there is a secret, Śrīla Prabhupāda is disclosing it as an open secret. In the passage here, he is stressing this salient point by repetition.

We have been informed that this secret will remain sealed if we hear Bhāgavatam from the skillful entertainer or academic. Now here we are given the positive injunction: we have to receive Bhāgavatam exclusively from “the representative of Śukadeva Gosvāmī.” Only under this condition will Bhāgavatam actually take place. “That is the process, and there is no alternative.”

Now Śrīla Prabhupāda elaborates on “the process:”

Sūta Gosvāmī is a bona fide representative of Śukadeva Gosvāmī because he wants to present the message which he received from the great learned brāhmaṇa. Śukadeva Gosvāmī presented Bhāgavatam as he heard it from his great father, and so also Sūta Gosvāmī is presenting Bhāgavatam as he had heard it from Śukadeva Gosvāmī.

Here the idea of paramparā—implicit (as we’ve already noted) in the first sentence of this purport—receives explicit elaboration with this recounting of the exemplary, valid transmission of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam from Vyāsadeva to Śukadeva to Sūta, in which each successor is able to deliver the texts “as he had heard it.” This idea is stressed here by repetition, and, by means of both form and content, the passage evokes the idea of consummate fidelity in reception and transmission. To “represent” is to faithfully re-present, present over again.

The remainder of the purport will be dedicated to explicating such flawless hearing— or, in our case, reading—and the method for attaining it. Thus:

Simple hearing is not all; one must realize the text with proper attention.

Not only do we have to hear from the right person, but we also must hear in the right way. A special kind of hearing is required in order for us to “realize the text,” that is, to hear in the same way that Sūta has heard it. That requirement for hearing, Prabhupāda says, is an especially heightened, concentrated attention.

Śrīla Prabhupāda elucidates this kind of attention by referring to the word niviṣṭas in the text, translated in the word-for-word-breakdown as “being perfectly attentive” and in the running translation as “rapt attention.” These renderings are in line with the word’s literal sense of being profoundly intent upon something or deeply absorbed in it. However, in the purport Śrīla Prabhupāda comments:

The word niviṣṭa means that Sūta Gosvāmī drank the juice of Bhāgavatam through his ears.

Here, Śrīla Prabhupāda specifically explicates this condition of eager attention by using a metaphor that likens the optimal hearing of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam with the avid, thirsty drinking of a deliciously sweet and refreshing nectar or juice.

The Sanskrit word for juice is rasa, and Śrīla Prabhupāda’s use of “drank the juice” directs the attentive reader’s memory back to the third text of Bhāgavatam (1.1.3), where the metaphor is explicitly employed in the text to characterize the hearing of Bhāgavatam. There the words pibata bhāgavataṃ rasam enjoins the audience to “drink the juice of Bhāgavatam.” In his commentary to that verse, Prabhupāda explains how the word rasa, as employed here, indicates the special transcendent flavors of variegated spiritual bliss relished by devotees through a fully developed relationship with Kṛṣṇa —bliss directly evoked and intensified by Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam when properly enacted.

Next, Śrīla Prabhupāda gives a concise restatement of the conditions and the result of such proper enactment, having made “rapt attention” explicit in this iteration:

That is the real process of receiving Bhāgavatam. One should hear with rapt attention from the real person, and then he can at once realize the presence of Lord Kṛṣṇa in every page.

(We should notice here how Śrīla Prabhupāda has once again conflated hearing and reading, just as he did in the purport’s opening sentence.)

Now Śrīla Prabhupāda proceeds to unveil to us even further the “secret” for the authentic realization of Bhāgavatam: He carefully elucidates the preconditions for the requisite “rapt attention”:

The secret of knowing Bhāgavatam is mentioned here. No one can give rapt attention who is not pure in mind. No one can be pure in mind who is not pure in action. No one can be pure in action who is not pure in eating, sleeping, fearing and mating. But somehow or other if someone hears with rapt attention from the right person, at the very beginning one can assuredly see Lord Śrī Kṛṣṇa in person in the pages of Bhāgavatam.

Here Prabhupāda divulges that the “rapt attention” necessary for proper assimilation of Bhāgavatam depends upon a prerequisite: purity of mind. And that condition, in turn, requires purity in one’s actions. And such purity in action must be so deep and pervasive that even the most basic biological necessities of animal existence—“eating, sleeping, fearing [i.e., defending], and mating”—are accommodated in a regulated, refined, and wholesome manner.

Here, ISKCON devotees can recognize an implicit reference to the way of life we commit ourselves to by the formal vows Prabhupāda requires of us for initiation: To chant at least sixteen rounds of the Hare Kṛṣṇa mahā-mantra daily on japa beads with care and attention, and to follow the “four regulative principles” of no meat eating, no intoxication, no illicit sex, and no gambling.

Śrīla Prabhupāda had published the first volume of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam in India three years before he

embarked for the United States; even so, we can discern in this purport the seed, the potential existence, of the temple-ashram that was to become manifest at 26 2nd Avenue in the lower East side of New York City, and indeed of the entire International Society for Krishna Consciousness that expanded from there.

This seed describes the conditions under which Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam can be manifest and transmitted. Only with a qualified speaker and qualified hearers—then and only then does Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam actually take place, and then only can one “assuredly see Lord Śrī Kṛṣṇa in person in the pages.”

Śrīla Prabhupāda brought forth his English rendering of the First Canto, in the sixth decade of his life, for a qualified audience of hearers that did not yet exist. His indefatigable labor in composition and publication of these three volumes—solitary, unassisted labor, underfunded, under appreciated—show the strength of his desire to give Kṛṣṇa consciousness to the entire world. But this desire is but the outer expression of his deep and fervent prayer to Kṛṣṇa to make such an audience available. And, quite remarkably, such an audience began to manifest and grow.

How, then, should we who have so benefited from Śrīla Prabhupāda’s prayer, who have joined that audience, demonstrate our gratitude? How can we repay him?

Śrīla Prabhupāda demonstrated the truth of Lord Caitanya’s characterization of His saṇkīrtana movement: ānandāmbudhi-vardhanaṁ, it increases the ocean of transcendental bliss. The prime reason for this increase is that Kṛṣṇa Himself is ever-increasing—in beauty, in opulence, in knowledge, in joy. There is no upper level, and we have been recruited, by Śrīla Prabhupāda’s mercy, to add to this everlasting expansion.

Let us therefore increase. We should all know the formula: As Kṛṣṇa consciousness increases, to that same degree, māyā, sense gratification, decreases. The two are inversely proportional. However, we can do even better than the formula allows. To the degree that we commit ourselves in action to that effort, to the same degree Kṛṣṇa and Śrīla Prabhupāda help us; so our sincere effort will produce an effect much greater than the cause. There is a divine thumb on the scale.

Engaging in this effort, we discover that Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam reveals itself to us more and more. By following the “four regulative principles” we discover that they are not merely principles of morality; they are, even more so, principles of knowledge—of knowledge unavailable to those who have little interest in the process of becoming “pure in mind.” So long as our established institutions of “higher learning” find this irrelevant to their core mission, their scientists and intellectuals will be unable to give true and proper guidance for the advancement of human society.

The knowledge contained in Bhāgavatam is not restricted to transcendence. It discloses Kṛṣṇa, and Kṛṣṇa means Kṛṣṇa and all of His energies, including his material energies.

Śrīla Prabhupāda put it like this in a 1971 London Bhagavad-gītā class:

Every one of us acquiring knowledge. That is called experience, one after another. So Kṛṣṇa says that ``If you understand this science,`` sa-vijñānam, ``then your knowledge will be complete. You have nothing to hanker after any further knowledge. Knowledge is complete.`` That is also Vedic injunction (Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad 1.3). Yasmin vijñāte sarvam evaṁ vijñātaṁ bhavati. Yasmin vijñāte, if you can understand the supreme knowledge, the Supreme, then sarvam idaṁ vijñātaṁ bhavati, everything becomes known to you.

In his Preface to his first volume of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, Śrīla Prabhupāda described his work as “a cultural presentation for the respiritualization of the entire human society.”

He made that mission his own, and now let us make it ours.

saranga thakur das

Posted at 12:01h, 12 Novemberpamho. agtsp.

thank you for a wonderful enlightening article

Syamakunda Das

Posted at 20:44h, 11 SeptemberVery well written. Hare Krsna